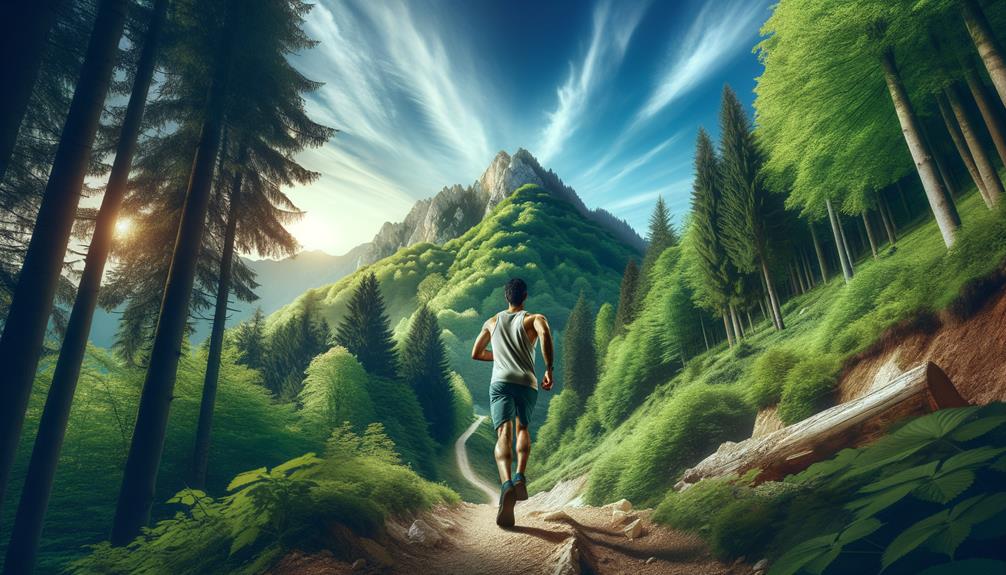

Achieve Your Fitness Goals: Proven Exercise Methods

When it comes to achieving fitness goals, the journey can often be as challenging as the destination is rewarding. Imagine ...

Read more

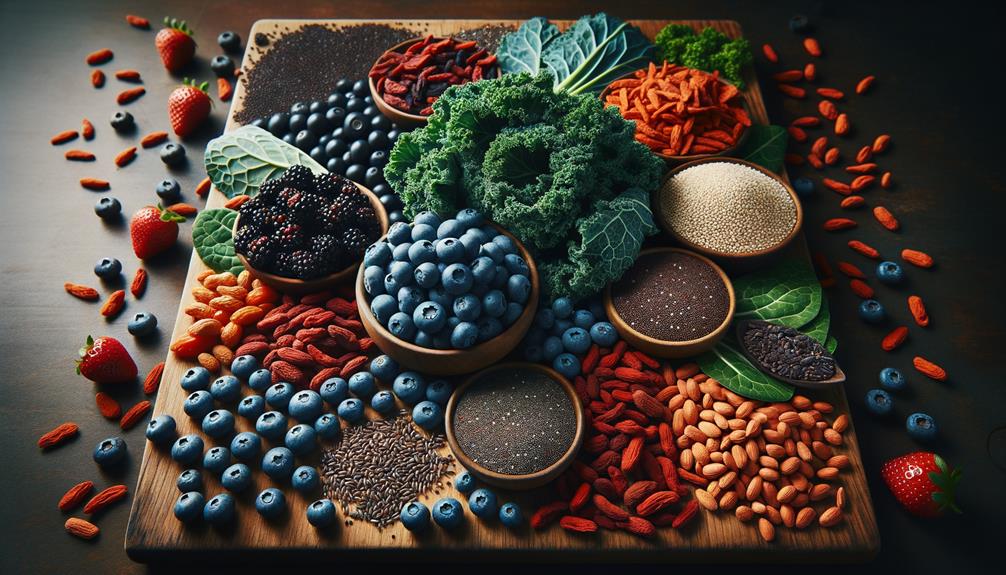

Nature's Superheroes Unveiled: Demystifying Superfoods

Many people may not realize that some everyday foods hiding in plain sight possess extraordinary health benefits that could rival ...

Read more

Maximizing Health Potential: A Guide to Vitamins & Supplements

Many individuals may not be aware that certain vitamins and supplements can interact with prescription medications, affecting their efficacy. Understanding ...

Read more

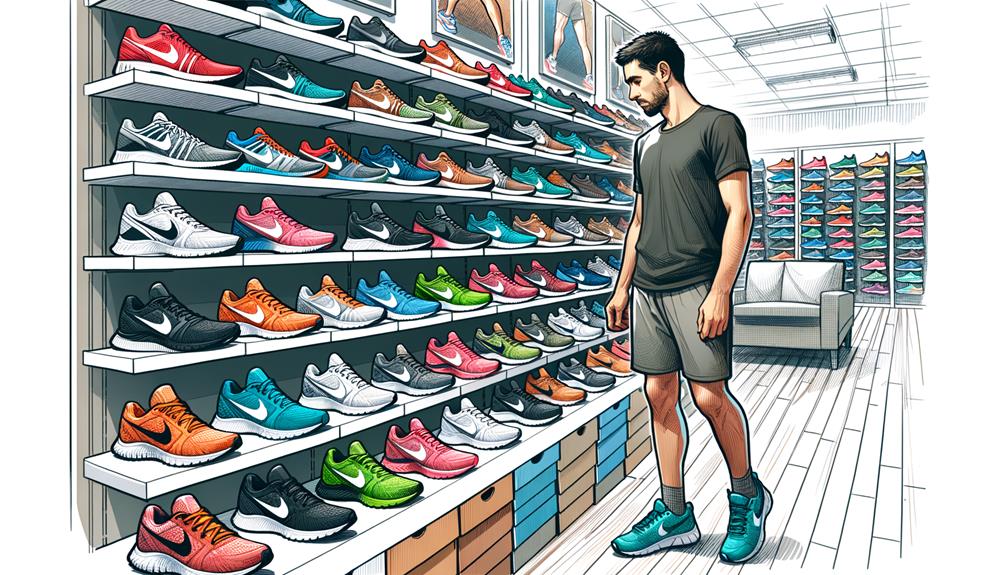

Beginner's Guide to Buying Running Shoes

When it comes to venturing into the world of buying running shoes, beginners often find themselves faced with a myriad ...

Read more

Elevate Your Health: The Power of Exercise

Recent studies have shown that only about 23% of adults in the United States meet the recommended guidelines for aerobic ...

Read more

Elevate Your Lifestyle: The Role of Vitamins and Supplements

Recent studies have shown that a significant percentage of individuals do not meet their daily recommended intake of essential vitamins ...

Read more

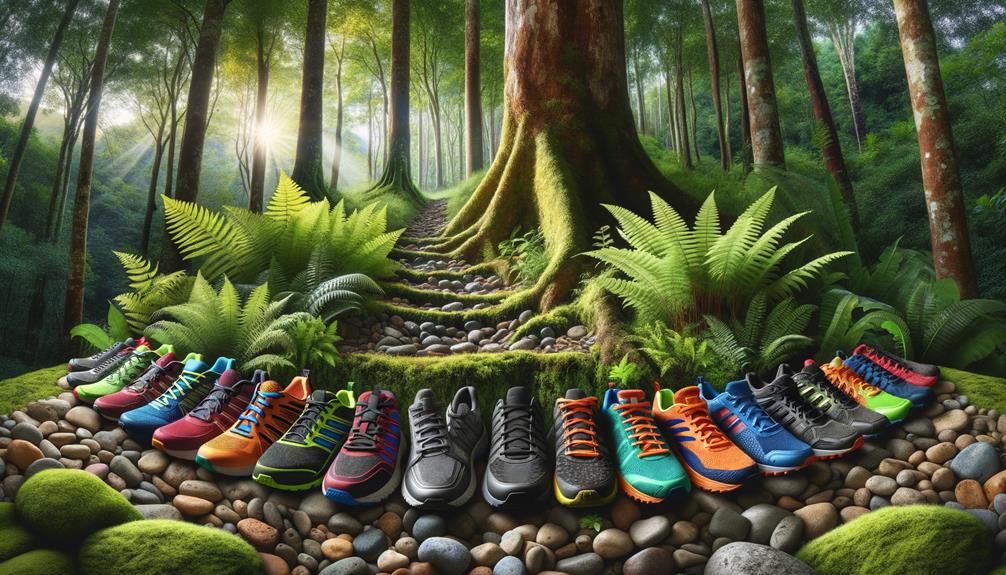

Top Picks for Trail Running Shoes

In the domain of trail running shoes, the search for the perfect pair can be a challenging one. However, one ...

Read more

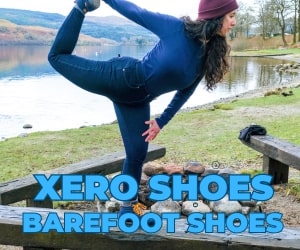

Xero Shoes Recovery: Selecting Ideal Post-Workout Footwear

Selecting Ideal Recovery Shoes Fit When choosing recovery shoes, prioritize a snug yet comfortable fit to ensure proper support for ...

Read more

Sculpt Your Body: Effective Fitness Techniques Revealed

To achieve a sculpted physique, individuals often seek out proven fitness techniques that can help them reach their goals effectively. ...

Read more

Supercharge Your Health: Exploring Superfoods Benefits

Many individuals may not realize that certain superfoods can offer a wide array of health benefits beyond basic nutrition. The ...

Read more

Unveiling the Power of Vitamins & Supplements

Revealing the power of vitamins and supplements opens a gateway to a world where tiny capsules hold the key to ...

Read more

Best Running Shoes for High Arches

When searching for the ideal running shoes for high arches, individuals often seek a perfect balance between support, cushioning, and ...

Read more

Unleash Your Potential: Essential Exercise Strategies

Sarah, a working professional, noticed a significant improvement in her energy levels and productivity after incorporating a structured exercise routine ...

Read more

Supercharge Your Wellness: Vitamins and Supplements Explained

Exploring the domain of vitamins and supplements can reveal a world of intricacies that many may not realize exist within ...

Read more

Ultimate Guide to Choosing Running Shoes

When it comes to selecting the perfect running shoes, the options can be overwhelming. From considering pronation and arch type ...

Read more

Boost Your Workout Routine: Exercise and Fitness Tips

In the pursuit of enhancing one's workout routine, understanding the importance of proper warm-up and cool-down techniques can make a ...

Read more

Unleash the Power of Superfoods: A Comprehensive Guide

Begin a journey towards a healthier lifestyle by tapping into the potential of superfoods. These nutrient powerhouses hold the key ...

Read more

Boost Your Health: Essential Vitamins & Supplements

Recent studies have shown that a significant percentage of adults do not meet their recommended daily intake of essential vitamins ...

Read more

Top 10 Running Shoes for Marathon Training

When it comes to marathon training, selecting the right pair of running shoes can make a significant difference in a ...

Read more